Brian Germain's Store

Nature Therapy Experiences, Holistic Life Coaching, Books, Parachute Flight Instruction, Parachutes, and more!

Core Mission

It our core mission to help humanity grow more courageous, heart-driven and harmonious in our cooperation with the ecosystem and each other.

Lotus Airlock Parachute Deposit

|

Parachute Designs by Brian Germain

*Plus $100 per size over 150 The Lotus is Big Air's medium performance 9-Cell parachute equipped with "Airlocks". Similar in some ways to the PD Sabre 2, the Lotus is a versatile airfoil that will please both conservative experienced skydivers, and newer jumpers looking for a safe canopy. The rigid feel of the wing is reminiscent of the Jedei, but without the severe "ground-hungriness" or radical turns associated with elliptical designs. Big Air's Canopies are now available as a Signature Series line only. That means that each one is hand-crafted by Brian Germain himself. Delivery times may vary, so contact us for details. Available sizes (sq. ft.)*: 95, 105, 120, 136, 150, 170, 190 *The Measuring technique is similar to that used by Performance Designs.

Wing-Loading "Wing-Loading" is the way in which parachute designers define the relationship of the weight of the skydiver to the size of the parachute. Wing Loading is measured in Pounds Per Square Foot (lbs/sf). We steer experienced and aggressive pilots toward the 1.4-1.8 lbs/sf range, intermediate and conservative pilots toward the 1.2 - 1.4 range, and beginner to intermediate skydivers are suggested to stay within the 1.0 - 1.2 range. Ultimately, exact wing-loading is a matter of preference and experience. Aspect Ratio "Aspect Ratio" is the relationship of a canopy's span (wingtip-to-wingtip) to it's chord (front-to-back). For example, a completely square parachute has an aspect ratio of 1.0. The aspect ratio of the Lotus is similar to the PD Sabre 2, (about 2.73 to 1, depending upon how you choose to measure it). This is slightly higher than the Samurai, which improves the glide and slows the turn-rate somewhat. Semi-Elliptical Planform "Planform" is the general shape of the wing when viewed from the top or bottom. Different shapes perform very differently, and a designer must choose the shape carefully in order to illicit the intended performance envelope. The Lotus has a dual-tapered planform, meaning that the leading and trailing edge both have a slight curvature. However, we have found that excessive curvature of the leading edge can lead to such negative attributes as opening problems, particularly in line-twists, as well as excessive "over-steer" (see next passage). Therefore, the ellipse used on the Lotus is tapered more on the trailing edge than the leading edge of the canopy. Keep in mind, however, that the slightly shaped planform utilized in the Lotus is absolutely minimal. The Lotus is, for all intents and purposes a rectangular planform, with a little shape to omit wrinkles and reduce the toggle pressure. Over-Steer "Over-Steer" is a wing's tendency to continue turning even after the control input is ceased. This "slippy-slidey" feeling is considered by most pilots to be a nuisance. Therefore, the Lotus has no over-steer following a toggle or riser turn. Slight over-steer characteristics can be elicited, however, using weight shift in the harness. Weight-Shift "Weight-Shift" is the use of deliberate leaning in the harness as a control input. Lifting your right knee will cause a left turn on most canopies, particularly ellipticals. The Lotus responds somewhat to a shift in C.G. to one side of the harness, but not as severely as the Samurai. By leaning into the turn, the pilot can increase the rate of dive, as well as the length of the recovery arc. Glide Ratio "Glide Ratio" is the flight path of a wing, measured in descent distance compared to forward progression. Unfortunately, this flight characteristic varies greatly with use and flying conditions, making it difficult to accurately quantify. We find it most useful to simply compare our canopies to others of similar design. The glide of the Lotus is similar to the PD Sabre 2, and flatter than the Samurai. Recovery Arc "Recovery Arc" describes the amount of time and altitude required for a parachute to recover to level flight following a radical maneuver. Although it is difficult to quantify this characteristic in a manner that would be useful, generalities can be very helpful when choosing a canopy. The Lotus falls somewhere between the PD Sabre and the Samurai in it's aggression to recover from a dive. In other words, the Lotus will dive for a time immediately following an airspeed-increasing maneuver, but gradually pull out on it's own to a slowly-descending, high-speed flight mode. This design characteristic makes the Lotus very easy to swoop successfully, as you are able to pick up speed at a high altitude, and then wait for the right moment to level off with a bump on the toggles. Compared to canopies that pull you to level flight before you are ready, the Lotus is much easier to land, and swoops further across the ground. Slow-Flight "Slow-Flight" is, as it sounds, a parachute's ability to fly slow without stalling or loosing directional control. The Lotus is very comfortable in deep brakes, with a very slow stall speed. This softens your touchdowns, and makes braked-approaches a possibility. Sweet-Spot The Landing Flare is the dynamic process of changing the canopy's angle of attack to level off and land. The "Sweet Spot" is the point in the toggle stroke that causes the parachute to fly level with the ground. A canopy that levels off below hip level tends to be considered harder to land. The Lotus has a fairly quick response to the toggles, allowing the pilot to level off with minimal input on the brakes. With normal wing-loading, the "sweet-spot" is about shoulder height. This location varies according to wing-loading, airspeed, and toggle-setting. Faster approaches require less input to level off, while slow approaches require more toggle movement to achieve level flight. With this in mind, the Lotus will land easier and softer when the pilot flies full-flight to flare altitude, and then applies the brakes quicker during the first phase of the flare to effect a decisive level-off. Starting the flare slowly at a higher altitude will only diminish the airspeed without causing the canopy to level off. Effectively then, you will have lowered the sweet-spot when you descend to the proper flare altitude. Construction/Materials All Big Air parachutes are made exclusively from Performance Textiles SOLARMAX fabric. No other fabric lasts as long, period. All the reinforcing tapes are extra strong, above and beyond what is customarily used in the skydiving industry. Our lines are Spectra, with the exception of the brake lines, which are made from Vectran. This proven method prevents shrinkage of the brakes, which prevents many of the problems caused by dimensional change associated with spectra brake lines. Our method of scaling and manufacturing linesets in unsurpassed in the industry, making every canopy fly exactly the same, without the hassle of built-in turns. The seams of Big Air canopies are the same utilized in many of Performance Designs newer designs, including the Velocity and the Vengeance. At Big Air we have a very simple philosophy on the longevity of our product: "We get customers by building the best parachutes in the world, not by having the old ones wear out." Precise Computer Cutting All of Big Air's canopies are designed and cut out by an advanced computer system. This affords us the ability to design more complicated and exact panel shapes, and cut them out with perfect consistency. You should expect nothing less from a company like Big Air. Few issues in parachute design have met with as much controversy as ram-air "Airlocks". Simply put, Airlocks are one-way valves in the leading edge of a ram-air canopy that maintain the internal pressurization. The intent of such valve parachutes is to prohibit instantaneous deflation of the airfoil, thus increasing the safety margin when flying in rough conditions. Although the author stresses that most of the ram-air canopies available today are very safe, the purpose of this article is to look toward the future of the ram air canopy, and the role that airlocks may play in this evolution. A discussion of the empirical and theoretical issues relating to valve parachutes. Origin of the Idea When I was spiraling toward the earth with an 80% collapse, there was not enough inflated nylon over my head to slow my descent, or allow me to recover prior to impact. The landing put me in a wheelchair for many months, leading me to take serious interest in the valve idea. As I explored the many variations of airlock ideas, I soon realized that the game was fairly simple: Gather as much pressure as possible, and seal the wing off when the air tries to escape. Hence, the Germain Airlock allows the air to enter the wing in its normal pathway, sealing against the top-surface when necessary. Discussion Despite the availability of airlock designs since 1994, more than eighty five percent of the canopies sold are still devoid of this invention. This may be due to a lack of information about the advantages of the airlock design. Many jumpers still don't know exactly what an airlock is. Others believe that airlocks are just another unnecessary gimmick. Supporting this counter-airlock philosophy is the belief that even cell pressurization is all that is necessary to maintain a parachute is stability. In order to look closer at this perspective, we must first define what is meant by the term stability. Primary Stability

This being said, the feeling of an airlock parachute in bumpy air is distinctly different from that of conventional designs. Since the air pressure maintaining the shape of the wing is relatively constant in an airlock parachute, the wing tends to distort and move around less than open-cell designs. This is very noticeable when flying in turbulence, during which an airlocked wing generally does not encounter significant span-wise oscillations, also called the accordion-effect. The bottom line in primary stability is, however, does the canopy stay at the end of the lines? Some parachutes clearly do not, regardless of whether or not they have airlocks. If you pull on the front risers on a canopy that has sufficiently long brake lines and it bucks wildly or the leading edge bends under, it has bad primary stability, at least in that configuration. In other words, you cannot just sew airlocks into any parachute and expect it to be better in every way. It is not that simple. Secondary Stability

Limits

Another limitation of the ram-air canopy is its ability to handle significant vertical air movement. A strong downdraft can increase your vertical speed beyond your canopy is ability to climb. Remember; even a rigid-wing airplane can crash in severe turbulence. There will always be a time for wise pilots to ground themselves. The old saying goes: It is better to be on the ground wishing you were in the air, than in the air, wishing you were on the ground. Conclusions All things considered, however, it makes a lot of sense that a parachute capable of maintaining its internal pressurization and surface area increases your chances of surviving. The most elegant, common sense ideas need little justification. Airlocks certainly fall into this category. We at Big Air believe that a ram air canopy is not complete without airlocks. A Canopy is simply Air shaped into a wing... No Air... No Wing. One must consider the fundamental definition of a cell. In biology, a cell is the smallest component of life as we know it. It is a self-contained entity, perhaps existing in cooperation with others, which defines itself in terms of its cell wall or cellular membrane a little bubble of energy. A living cell defends itself from outside forces, and therefore perpetuates its own existence. This is life at its simplest. A dead cell has no complete barrier to the outside world. It allows its internal volume to ebb and flow, amorphically maintaining equilibrium with the outside world. By airlocking a parachute, we give it a life of its own, and it will fight to stay alive. Do airlocks increase the safety of the ram-air parachute? In most cases, yes. It is very similar to wearing a seatbelt on take-off. There are no guarantees that we will walk away from a crash, but I still always wear one. Many skydivers will continue to take a wait and see approach to airlocks, and this conservatism clearly has a strong component of sanity. Nevertheless, six years and over 2000 airlock canopies certainly are a compelling amount of evidence... |

About Us

Brian Germain

store owner

Brian Germain is one of the most well known skydiving instructors in the world, and a multinational voice on the topic of holistic wellbeing. With tens of thousands of jumps over 40 years of continuous skydiving and adventure travel, Brian has learned much he can share to help you to become a happier, healthier, more effective human being. His many years of psychology study and many years of work as a Holistic Life Coach will provide you with a refreshing, uncommon perspective.

Brian's work on the topic of fear and its effects became crystallized in 1993 when tragic paraglider collapse nearly took his life. Rejecting the doctors’ proclamation that he would never jump again, Brian not only emerged from his wheelchair to continue skydiving, but just a few years later became the ESPN X-Games World Champion in Freefly Skydiving. His inspiring journey through and beyond fear has moved people all over the world to challenge their own personal boundaries, and expand who they are through taking fear head-on.

Brian's amazing recovery has led him to author numerous inspiring books and articles about overcoming fear and life challenges, including his best-seller Transcending Fear, the inspiring Green Light Your Life, Vertical Journey, and the world-renowned textbook of skydiving, The Parachute and its Pilot. His passion for the topic of fearless living has resulted in a barrage of interviews with the media, as well as his inspiring business keynote talks and experiential workshops. Brian's journey through apparent impasse has led him to many refreshing insights that will provide you with powerful secrets for handling stress in all its forms.

Brian Germain has dedicated his life to the study of fear and its antidotes, but what distinguishes him from others on similar paths is his unique ability to tell the story in an enjoyable way. His animated expression of this challenging aspect of the human experience is both profound and useful, and surprisingly funny. Brian's uncanny ability to paint the picture of the archetypal journey from fear to heroism has been fostered by many years of compassionate skydiving instruction.

Brian got his start as an Adventure Guide with Longacre Expeditions, focusing on rock climbing and mountaineering. After earning a BA in Psychology from the University of Vermont, Brian founded "Vermont Skydiving Adventures" parachute school at the age of twenty five, which he owned and operated for several years. At this small operation on the Canadian border, Brian trained many now-world-renowned skydivers with his unique and heart-driven methodology.

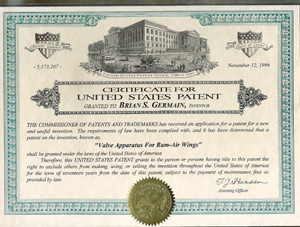

That is when his tragic paraglider collapse changed his life forever. For the next two years, Brian had to focus his efforts on the physical and mental healing process. As part of his path to recovery, he set his sights on preventing the same tragedy from befalling other parachutists. He faced his own fear by returning to the sky to test his own collapse-resistant "Airlock" prototypes, eventually founding his parachute design company BIG AIR Sportz. Brian's innovative work earned him a Patent for "Valved Apparatus for Ram-Air Canopies" (US Patent #5,573,207), a design that has been utilized in thousands of parachutes all over the world. He continues to build and test advanced parachute designs in order to improve safety and efficiency.

After writing the definitive book on parachute aerodynamics and safety, The Parachute and its Pilot, Brian created his world-renowned Parachute Flight Skills and Safety Course, an advanced training workshop for civilian and military parachutists. Brian continues to tour the world teaching parachuting safety, and is also the host of the very popular radio show entitled "Safety First with Brian Germain" on SkydiveRadio.com, as well as "BG Live", a revolutionary online training program on found at AdventureWisdom.com.

Brian Germain has many messages of great value from which anyone can benefit. The wisdom and positive outlook he has gathered applies directly to every aspect of life. The core skills that he teaches can help you to thrive in the midst of the most ominous leadership challenges, and help you to establish an emotional buoyancy that will make you the kind of person that others want to follow.

For Scheduling: Brian.transcendingfear@gmail.com (301) 646-0761

Transcending Fear is a Leadership Training Company. Our main offerings include: Fear Seminars by a noted Fear Expert for overcoming fears, Leadership Training Workshops, a celebrity Skydiving Instructor for skydiving fear challenges, and Skydiving Videos and Skydiving Books by Author Brian Germain.

Common Tags: Author Motivational Speaker, Fear Expert, Nature Guide, Forest Therapy, Forest Bathing, Nature Meditation, Skydiving Instructor, Keynote Speaker, Professional Skydiver, Inspirational Speaker, Business Motivational Speaker, Fear Author, Corporate Motivational Speaker, Skydive Instructor, Celebrity Skydiving Instructor, Skydiving Adventure, Skydiving Experience, Skydiving Training, Skydive Courses, Skydiving Safety, Skydiving Jumping, Top Motivational Speaker

©2006-2025 Brian Germain. All Rights Reserved

First there is what may be termed Primary Stability. This is a ram-air canopy is ability to remain in control and under adequate line tension during normal flying conditions. Primary stability is generally attributed to the airfoil shape and the line trim configuration. This is the result of painstaking testing and adaptation, as generalities are often disproved when applied to different designs. Primary stability includes everything from slow flight to accelerated flight modes as well as pilot-induced airfoil distortions such a front-riser input.

First there is what may be termed Primary Stability. This is a ram-air canopy is ability to remain in control and under adequate line tension during normal flying conditions. Primary stability is generally attributed to the airfoil shape and the line trim configuration. This is the result of painstaking testing and adaptation, as generalities are often disproved when applied to different designs. Primary stability includes everything from slow flight to accelerated flight modes as well as pilot-induced airfoil distortions such a front-riser input. Secondary Stability is the term that can be applied to how a parachute responds to catastrophic situations such as a bent wing or full-frontal collapse. In some situations, properly designed airlock parachutes can make a difference, keeping the wing inflated and ready to resume stable flight. If, however, the unstable air is encountered very close to the ground, airlocks may not be enough. In fact, one must realize, there are atmospheric circumstances in which a metal wing may not be enough. The philosophy of the valved parachute design is that a wing that has air in it can reduce the risks of total surface area loss, but not eliminate the possibility of serious injury. Sometimes no amount of preparation or technology is enough.

Secondary Stability is the term that can be applied to how a parachute responds to catastrophic situations such as a bent wing or full-frontal collapse. In some situations, properly designed airlock parachutes can make a difference, keeping the wing inflated and ready to resume stable flight. If, however, the unstable air is encountered very close to the ground, airlocks may not be enough. In fact, one must realize, there are atmospheric circumstances in which a metal wing may not be enough. The philosophy of the valved parachute design is that a wing that has air in it can reduce the risks of total surface area loss, but not eliminate the possibility of serious injury. Sometimes no amount of preparation or technology is enough. Several limitations are handed to the parachute designer that other aeronautical engineers need not consider. One such challenge concerns the suspension lines. Your suspension system is flexible, allowing for line-twists and line-slack. A canopy locked into an asymmetric configuration will most certainly exhibit an extreme spiral accompanied by a rapid loss of altitude. Line-slack due to improper pitch-control or aggressive maneuvering can also create unknown variables that can lead to accidents. Maintaining line tension on any parachute is essential for minimizing the risks of catastrophic failure. We minimize the risk of slack lines by executing smooth control inputs, and smooth release of input as well. Modern ram air canopies require much more than just pulling toggles, we are required to fly them.

Several limitations are handed to the parachute designer that other aeronautical engineers need not consider. One such challenge concerns the suspension lines. Your suspension system is flexible, allowing for line-twists and line-slack. A canopy locked into an asymmetric configuration will most certainly exhibit an extreme spiral accompanied by a rapid loss of altitude. Line-slack due to improper pitch-control or aggressive maneuvering can also create unknown variables that can lead to accidents. Maintaining line tension on any parachute is essential for minimizing the risks of catastrophic failure. We minimize the risk of slack lines by executing smooth control inputs, and smooth release of input as well. Modern ram air canopies require much more than just pulling toggles, we are required to fly them.